“Stalking is immoral but not illegal”: Understanding Security, Cyber Crimes and Threats in Pakistan

Authors: Taha and Afaq Ashraf (TODO affiliations)

Problem/Motivation

While the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated internet growth and made life easier for the masses, it increased the incidence of cybercrime worldwide. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) reported receiving 17,000 cybercrime-related complaints in 2020, a 40% increase compared to reports received in 2019. Among many, young adults (aged between 15-24) were a prime target of cyber attacks. This demographic contributes to 19% of all internet traffic in Pakistan. It was intriguing that a tech-literate and digitally savvy population could be victimized at scale.

What we did

In our study, we attempted to unpack the cybercrime experiences and perceptions of young adults in Pakistan through a nationwide qualitative and repertory grid technique (RGT) study. We tried to answer what is considered cybercrime from the lens of these young people, what mechanisms they use to ensure their digital security, and what behaviors they exhibit when reporting cyber attacks.

To accomplish this, we conducted 18 RGT interviews (13M, 5F) and 34 qualitative interviews (17M, 17F). In the RGT study, we presented the participants with cybercrimes as elements and instructed them to compare and contrast the presented elements. The end product after each interview was a repertory grid. A diagram explaining the methodology can be seen below:

The qualitative interviews aimed at exploring information about the participants’ device and internet usage, their experiences and beliefs regarding cybercrime, and reporting mechanisms.

Main findings

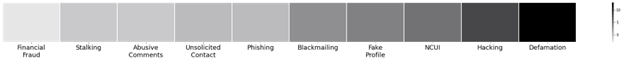

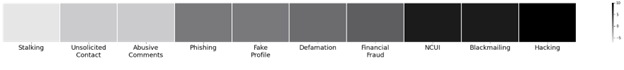

Using the data from the RGT study and qualitative interviews, we created a dis-aggregated spectrum of cyber threats from least severe to most severe for male and female participants. The spectrum revealed gendered differences in the perception of cybercrime, with females finding defamation, hacking, non-consensual use of information (NCUI), and fake profiles as severe, and male participants finding hacking, blackmailing, NCUI, and financial fraud as harmful.

The qualitative interviews helped contextualize the spectrum. We found that female users are predominantly harmed through violations negatively impacting their reputations or those of their families, like defamation, fake profiles, or NCUI. In contrast, male users are often more concerned with financial fraud and hacking often because, in Pakistan, they are responsible for finances and actively conduct financial transactions.

Moreover, participants experienced significant barriers when reporting cybercrimes. The reporting mechanisms on social media platforms are ineffective in resolving complaints due to delayed responses. We also found a large mistrust of participants in government agencies. The root cause was revealed to be complex procedures and uncooperative staff. Lastly, the participants hesitated in reporting cybercrime to prevent stress by family members.

The study also highlights that users are highly aware of platform-level vulnerabilities, but they often lack knowledge regarding platform affordances that can enhance their security. To counter this, we propose that platforms consider switching to an opt-in default approach, whereby privacy preservation is the default setting. In addition, context-based onboarding procedures could be implemented for customized onboarding procedures.

Conclusion

Our research underscores the importance of understanding and incorporating specific cultural and religious values into the design to allow diverse users to freely use online spaces. It rings the alarm on the adverse reporting procedures of social media platforms and proposes practical design implications for the equitable design.

This blog post discusses our recent research paper “Stalking is immoral but not illegal”: Understanding Security, Cyber Crimes and Threats in Pakistan”, which will be presented at SOUPS 2023 in August.